Proposal for Jewish Resettlement

Between the years of 1939 and 1945, thousands of Jewish people sought refuge around the world from the Nazi regime in Germany and Europe during World War II. United States government officials attempted to devise a plan that would simultaneously bolster local economies and provide a haven for Jewish refugees seeking asylum. That haven was Alaska.

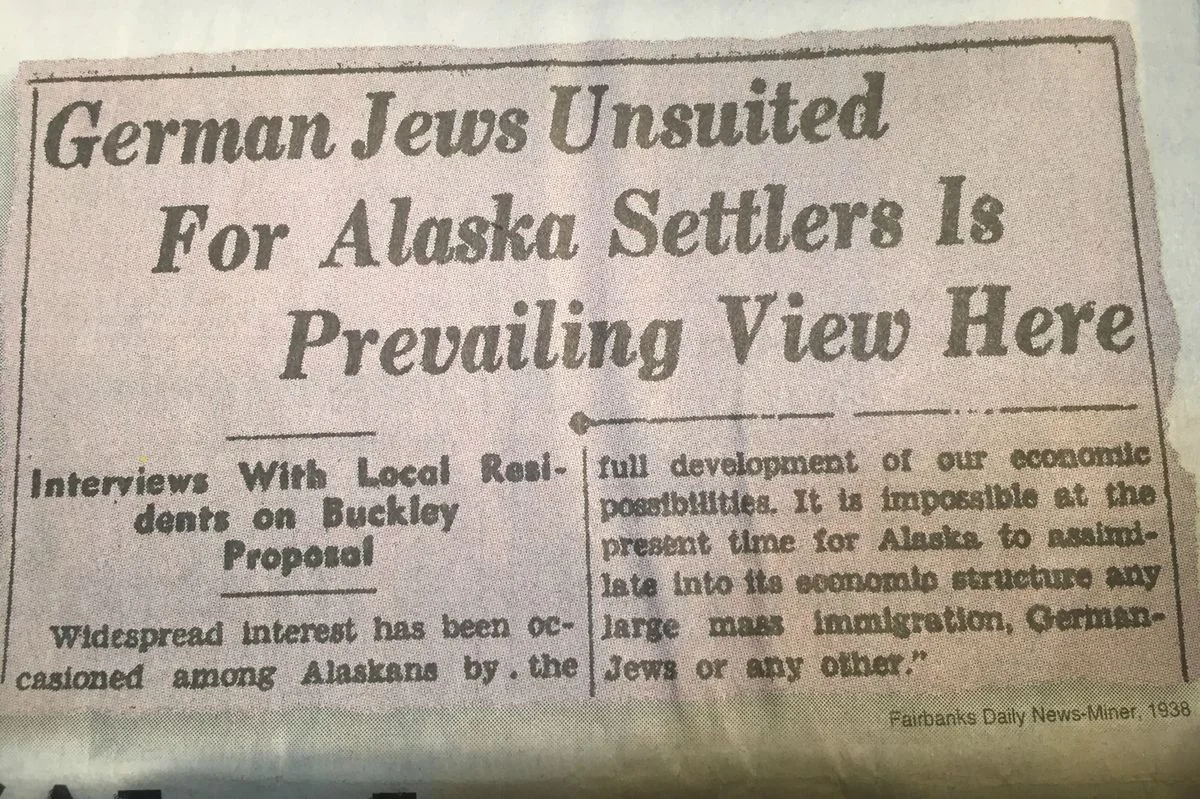

Clipping from the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner in 1938, showing widespread rejection of the Slattery Report proposing Jewish resettlement in Alaska. From: https://www.adn.com/resizer/qGDLvnMFYUP7RgYJC2Eu5KT4__8=/1200x0/wp-adn.s3-website-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/image-archive/1085021/refugees3.JPG?token=bar

The Slattery Report

In 1938, United States Department of the Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes visited various parts of Alaska to determine whether or not he would support a proposal to designate the Alaska Territory as a resettlement sanctuary for Jewish refugees from Germany. Because Ickes believed much of Alaska to be uninhabited and underdeveloped by governmental standards, and because he believed that mass Jewish resettlement could potentially strengthen security in a U.S. Territory then deemed vulnerable to attack, he moved for Interior Undersecretary Harry A. Slattery to author a report: The Problem of Alaskan Development. The proposal advocated for the relocation of incoming European refugees into four main parts of Alaska. The report included multiple points of contention, and it divided government leaders and community members at the time.

1939 Alaska: Territory, not state

Prior to World War II, strict quotas had been implemented in United States immigration law. However, because Alaska had not yet become a state, Ickes, Slattery and others who supported resettlement argued that refugees would be able to immigrate to the designated Alaskan territories but not the rest of the United States, therefore bypassing quotas previously established for the country. However, this provision quickly received criticism from the U.S. State Department, which contended that allowing "non-quota immigrants to enter Alaska would lead to the breakdown of the entire system of protective immigration law" (Berman 271). Then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was also hesitant about the Slattery Report. Although he largely supported rescue efforts, he worried that the sheer number of German Jews seeking asylum would be cause for political threat. Thus, Roosevelt publicly restricted the number of incoming refugees to 10,000 a year, for five years, and required that a maximum of 10 percent of that population be Jewish. He never mentioned Alaska or the Slattery Report in his public addresses. Without presidential backing, the plan was soon disbanded.

A failed 'experiment'

The State Department and FDR were not the only prominent voices to reject Ickes and Slattery's proposition. Once published, the Slattery Report was widely criticized by local officials, media and residents in Alaska, as well as a sizable number of prominent leaders in the Jewish American community at the time. Rabbi Stephen Wise, who was then the head of the American Jewish Congress, is noted as saying that the Alaska plan "makes a wrong and hurtful impression...that Jews are taking over some part of the country for settlement" (Medoff 2007). Conversely, anti-Semitic rhetoric was also a prominent opposing voice to the resettlement plan. In a piece titled "German-Jews Unsuited for Alaska Settlers is Prevailing View Here," published in the the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner on November 21, 1938, Alaskan residents are quoted as saying, "A Jewish group or any other racial group of aliens would not be able to maintain themselves in Alaska." And in a 1939 Daily News-Miner editorial: "Alaska wants no misfits, and none who are unprepared to make their way without becoming a burden upon the territory." Thus, despite attempts to garner more support, the Slattery Report fell short of federal acceptance.

Though the Jewish resettlement plan never came to fruition in Alaska, an exhibit in the Alaska Jewish Museum highlights that, in the late 1940s and early 50s, Alaska Airlines pilots helped airlift Jewish refugees to Israel, risking their jobs to do so. Courtesy of the Alaska Jewish Museum; "Alaska's Contribution to Operation Magic Carpet" exhibit. From http://www.alaskajewishmuseum.com/exhibit.

the king-havenner bill (s. 3577) &

'charity begins at home'

Adamant that a refugee resettlement plan would be crucial to the economic development of Alaskan resources, Ickes continued pushing for his proposal despite strong opposition, eventually garnering partial support from leadership within the DOI. In 1940, the King-Havenner Bill—or the Alaskan Development Bill—was introduced to Congress, encompassing some of the ideas from the Slattery Report, but repositioning its intentions toward "the establishment of privately financed public-purpose corporations" (Berman 272). The legislation espoused a 'charity begins at home' argument, stipulating that "50 percent of the newly created jobs would go first to unemployed qualified American citizens. Then, up to, but not necessarily, 50 percent of the remaining jobs would be filled by selected non-quota immigrants; that is, immigrants beyond their national quota numbers who would be permitted into Alaska" (272). Due to a lack of public support for further technicalities proposed by the bill surrounding the immigration provision, it died while in a review by the Senate Committee on Territories and Insular Affairs in May of 1940. However, the desire to "colonize Alaska for purposes of national defense and as a market for surplus product" remained even after the initial legislation died in Congress, and further requests and reactions towards European refugee resettlement in Alaska persisted throughout the postwar period (272-273).

'terra nullus', Settler colonialism & indigenous displacement

Throughout all of the 1930s and 40s discourse around using Alaska Territory as a place for Jewish and European refugee resettlement and economic development, the glaring point of contention repeatedly left out of conversation was the fact that Alaska Native communities had in fact inhabited the land for centuries prior to European settler colonization, and were not consulted prior to the plan's initiation. Today, literature surrounding the Slattery Report, and the reactions of U.S. citizens to the proposal, are devoid of critical commentary regarding the impact such a proposal may have had on Indigenous Alaskan populations.

This page urges readers to draw the following connections in order to view the proposal for Jewish resettlement through a critical lens. First, it is noted in the Slattery Report and other documents that Harold L. Ickes saw the potential of refugee resettlement in Alaska as a chance to 'bolster the economy', implying that his motive was less humanitarian in nature and more intent on using immigrant and refugee labor to capitalize on 'underdeveloped resources.' Such a dichotomy is reminiscent of the myth of terra nullus—meaning "a land without people"—which European settlers deemed the North American continent to be upon their first arrival (Dunbar-Ortiz 3). Second, as seen in the news clipping from the 1938 Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, a paradox exists in the reactions of 1938 Alaskan inhabitants who were quoted as denouncing the possibility that any incoming foreign refugees could survive in Alaskan territory or contribute to the community's infrastructure. Yet, these same residents were also not indigenous to Alaska, considering that many of them had in fact settled there as immigrants themselves, or were the descendants of such.

Thus, the Slattery Report proposal for Jewish resettlement in Alaska is situated within the United States' ongoing history of manifest destiny, settler colonialism, and mass genocide and displacement of indigenous communities.

Related Pages:

Sources:

Berman, Gerald S. “Reaction to the Resettlement of World War II Refugees in Alaska.” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 44, no. 3/4, 1982, pp. 271–282., www.jstor.org/stable/4467186.

DuBois, W.E.B. “White Masters of the World”. The World And Africa . New York: International Publ. (1972), pp. 16-43.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. “Introduction: This Land” in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. (Boston: Beacon Press) pp. 1-14 (2014).

Eshkoli-Wagman, Hava1. "Did the American Jewish Press Torpedo Rescue Opportunities? Resettlement Plans for Jewish Refugees in Alaska and the Dominican Republic, 1938-1943." Modern Judaism: A Journal of Jewish Ideas & Experience, vol. 35, no. 1, Feb. 2015, pp. 83-107. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1093/mj/kju018.

Kizzia, Tom. "Part One: 'Beacon of Hope' Sanctuary–Alaska, the Nazis and the Jews."; "Part Two: 'Give Us This Chance' Sanctuary–Alaska, The Nazis and The Jews."; "Part Three: 'Alaska Wants No Misfits' Sanctuary: Alaska, the Nazis and the Jews."; "Part fFour: 'Are There No Exceptions?' Sanctuary–Alaska, the Nazis and the Jews." Anchorage Daily News [AK] 16, 17, 18, 19 May 1999: A1. Business Insights: Essentials. Web. 27 Feb. 2017

Kizzia, Tom. "Novel Involving an Alaska Jewish Colony is Rooted in History." McClatchy - Tribune Business News Apr 26 2007: 1. ProQuest. 27 Feb. 2017 .

Medoff, Raphael. "A Thanksgiving plan to save Europe’s Jews." Jewish Standard. N.p., 16 Nov. 2007. Web. 28 Feb. 2017. <http://jewishstandard.timesofisrael.com/a-thanksgiving-plan-to-save-europes-jews/>.

"On the Wings of Eagles." Alaska Jewish Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2017. <http://www.alaskajewishmuseum.com/exhibits>.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8(4): 387-409.

https://nycstandswithstandingrock.wordpress.com/standingrocksyllabus/